The single most important thing you do every second of every minute of every day is breathe. Your breath powers every cell in your body. It is intimately tied in to your emotional states and energy levels. The health of every single part of your body is utterly dependant on it. So why on earth aren’t Doctors taught about the power of breath to change your physiology?

Learning to breathe properly is the single most important thing you can do to improve your general health

Where does your breath go?

Whereabouts in your body do you habitually breathe? High in the chest, around the middle or deep into the belly? Take a few breaths now and feel where it goes. Where do you feel most of the movement from the breath?

Most people find that they tend to breathe into the middle or upper part of their chest. Chest breathing is an inefficient means of bringing in oxygen. Some people breathe very high up in their chest, so high that their collar bone (clavicle) moves up and down with the breath. They are called clavicular breathers, and these people tend to be prone to high levels of anxiety and panic attacks.

Your lungs are cone-shaped, with the narrowest part at the top and the widest part at the bottom. Using chest or clavicular breathing can only fill up the smaller top part of the lungs, and so only a small amount of oxygen can be absorbed by the blood. It also means an equally small amount of CO2 can be breathed out. This means you have to breathe faster to maintain your oxygen and pH levels. You are using the intercostal muscles in your ribs to breathe, and overusing them will cause tension all around the upper body.

To breathe efficiently and so bring in more oxygen to your starving cells, you need to learn to draw air down to the lowest part of your lungs. Fortunately, we have a muscle that is designed to do that job and it happens to be one of the strongest muscles in your body. Unfortunately, in many cases it is used so rarely that it’s virtually paralysed from lack of use. It is called the diaphragm.

The muscles of breathing

Let’s take a brief look at the muscles involved in the breathing process and how to breathe more efficiently. Note that these are the physiological basics, and there is much more to the breathing process than this.

Your diaphragm is your most important breathing muscle and perhaps the most important muscle in your body.

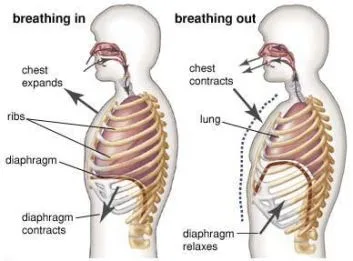

It is a sheet of muscle that stretches across the bottom of the rib cage. When contracted it pulls downward, drawing air deep into the lungs and fully oxygenating the blood. Your diaphragm is such a strong muscle that, when you learn to use it properly, it helps push blood around the lower part of your body, thus acting as a second heart. It has more surface area than the heart muscle and, as it pulls down, it strongly compresses the organs in the abdomen and pushes large amounts of blood through the system. This takes a large load off your heart and, with practice, can help reduce your heart rate and normalise blood pressure.

Basically, when you inhale you should use your diaphragm to pull air into the bottom of the lungs and expand your chest to complete the inhalation. The chest muscles (intercostals) are really secondary to the diaphragm so, at rest, it is often just the diaphragm that is necessary for the breathing process.

To exhale you reverse the process, relaxing the chest muscles and the diaphragm. This will shrink the chest cavity, pushing air out of your lungs. There is a problem here, though, and it is to do with our old friend, the tension paradox. To exhale is again a passive process; you breathe out by releasing tension in the diaphragm and intercostals, but how do you know how relaxed they have become? Of course you can’t, as you know from the tension paradox.

Your diaphragm is probably holding on to more tension than any other muscle in your body.

Most people barely use their diaphragm at all as it is so rigid with tension. This is a shame, as your diaphragm is one of the most powerful muscles in your body.

The reason why your diaphragm is probably frozen with tension is simple – it is stress. When you are under stress, one of your natural instincts is to hold your breath. I’m sure you have noticed this. You can go several seconds without breathing and without even noticing that you’re holding your breath. Hence the diaphragm contracts and stays contracted at the slightest sign of stress. Gradually it loses its flexibility and thus its function. More and more, your breathing takes place higher up in the chest, with the diaphragm occasionally waking up to assist in a big yawn.

For some people, deep diaphragmatic breathing can be a bit scary as it feels as if you are exposing a vulnerable part of yourself, but you must work through this if you are to progress. As I mentioned in the introduction, the body and mind are reflections of each other and opening up the deepest parts of the body can open up the deepest recesses of the mind. It is possible that you may regain memories of past traumatic episodes, experience nightmares or sudden emotional releases such as bouts of anger or tearfulness. Often these traumatic events occurred at a time when you weren’t emotionally mature enough to deal with the trauma, and so you locked it away deep inside you until you were better able to deal with the pain.

If you have a good support system such as family and close friends who can help you through this, then now may be that day. It is unlikely, however, that much emotional trauma will be stirred up by the breathing process but it is wise to take note of your emotional stability when you first start opening up and breathing into the abdomen. Believe me, I’m not trying to put you off attempting this.

The advantages of good breathing far outweigh the unlikely outcome of having to deal with some repressed emotions.

Using your breath to tone your stomach

Another reason why the diaphragm gets little use is our obsession with having a flat belly. Abdominal breathing means there is a slight expansion of the stomach area in all directions as we inhale, then it returns to the usual position. It isn’t really noticeable, but for many people the idea of letting their stomach out is a big no-no. This isn’t really a good excuse for not belly breathing for, as we shall see, correct breathing and posture will actually make you look and feel slimmer and tone your stomach muscles as well.

The relaxation of the intercostals and the diaphragm is not the end of the exhalation process. We should also get into the habit of using our abdominal muscles to push a little more air out with every breath. This also has several benefits. It empties the lungs further which allows more oxygenated air to be processed, it further massages the internal organs, thus keeping them functioning more efficiently, and it maintains tone in our abdomen – which, in itself, is a fitness goal for many people.

For these reasons, the diaphragm tends to be used very little by the majority of people. Generally those who do use it have to be re-taught to do so in qigong or yoga classes. Let’s change that right now and see if we can get that large and powerful muscle moving.

In all the following breathing exercises, remember the 70% rule. Don’t attempt to force as much air in or out as you can. To do so will cause tension in the abdominal and surrounding muscles, and tension is what we’re trying to avoid. Breathe no more than about 70% of your capacity. At the moment, if you’re like most people you are only using about 20–30% of your lung capacity anyway, so 70% is a huge improvement. This 70% rule applies to all the other exercises as well.

This next exercise teaches you how to breathe in the most efficient manner. It uses all the correct muscles for breathing and so enables a full and effortless breath. The diaphragm, as it pulls down, draws air into the lungs and as it relaxes it moves back up again, but this action only partially empties the lungs. To empty them more fully requires the use of another set of muscles – your abdominals.

For a long time now the abdominals have been a favourite target of fitness routines and magazine articles. However, one of their principal uses is in enabling a full exhalation.

Finding your diaphragm exercise

The aim of this exercise is to start mobilising the whole abdominal area. This will help loosen up the diaphragm and also help bring fresh blood to the digestive system and massage the internal organs. This helps enormously with problems such as constipation as it helps get things moving again. As with all breathing exercises, don’t attempt to do so on a full stomach.

- Ensure your lungs are relaxed (about half full). Lie down on your back in a comfortable position. This will keep you in a stable position and allow gravity to help loosen the abdominal area.

- Without breathing pull your stomach in towards your spine and upwards slightly under your ribcage. Then push it out again to full distension. Keep pulling it in and pushing it out slowly and smoothly until you need to take a breath. This will work the diaphragm and start to increase its movement

- Take a few nice slow deep breaths to stabilise your breathing then try again. Your aim is to try to feel the upward and downward movement of the diaphragm itself. Eventually you will be able to isolate its movement which will be of great help to your breath development.

- Now incorporate the movement into your breathing. As you breathe out pull your stomach in and up and as you breathe in allow the stomach to expand out somewhat. Don’t just push it out to the front but expand it to the sides and into your lower back as well. With some practice you will be able to increase your lung capacity and pressurise your abdominal area which will support and massage all the organs of digestion. It’s also a key part of serious power training. (see warning below)

- Now you need to incorporate this breathing practice into your everyday life. Spend a few moments regularly each day being aware of your breathing and incorporate the abdominal breathing regimen as detailed above. Soon it will become a very healthy habit.

Points to remember

If at any stage you start to feel light-headed then stop immediately and return to your normal breathing. However, don’t give up the practice because the light-headed feeling indicates that your brain has taken in more oxygen than it is used to receiving. Take a break for a while then continue later and soon the feelings of dizziness will go as your cells get used to a higher level of oxygen.

After having spent a few minutes on this exercise, you may notice some or all of the following: feeling light-headed (as mentioned above), increased energy (from the extra oxygen), or feeling very tired and/or relaxed.

You should have managed to feel your abdomen rising and falling as the diaphragm pressed down as you breathed in, pushing your belly out, then relaxed, allowing gravity to push your belly back in again.

Learning to breathe with your diaphragm is of vital importance for your health. It should be one of your primary goals to gain control of your diaphragm and make diaphragmatic breathing the habitual way you breathe. This may take a few days, even a few weeks but the benefits are profound. By taking control of your breath you take control of your physical and emotional health. It really is that simple.

Find out more about traditional Chinese health practices to develop a relaxed and powerful body and a focused mind through the tai chi and kung fu classes I run or sign up to our site to learn the wealth of material we have here.